EDIT: Credit where credit is due: I stole many of these ideas from Sean Lawson. Except they are better with FOSS.

The year 2020. Damn. Damn, damn, damn, damn.

Put it in the dumpster, man.

But the end of the worst year ever is also the end of the 2010s, so maybe now's a good time to reflect on my past decade as a FOSS Academic. As I mentioned in the Introduction, I've been using FOSS tools to do my job as a university professor for over a decade. Now, I'm looking ahead to the next decade.

Here, I want to document my workflow. It's a combination of desktop environments, workspace management, weekly planning and long-term goals. I've been developing it over the past decade, and I think it's time I formally document just how I do what I do.

It's a longish post, but then again, we're talking about practice. That gets complex!

Workspaces

No matter the underlying distro, I use the MATE desktop environment, which has a handy workplace switcher applet. This is fine, but out of the box is missing something.

Enter Devil's Pie. It's not just a documentary about the R&B singer D'Angelo. Devilspie is a small application that gives me total control over how applications load into various workspaces.

On my typical MATE setup, I have 6 workspaces. I'm old-school, so I set them up horizontally in a top panel. I also set my keyboard shortcut to CTRL+Left or Right to switch between them.

One of the first things I do is install devilspie and set it to run on startup.

Devilspie works with scripts stored in ~/USER/.devilspie. Each application requires its own script (saved in .ds files). For example, my Firefox script is:

(if (is (application_name) "Firefox") (set_workspace 3))

That line is in a file called firefox.ds, and as you might have guessed, opens Firefox in Workspace 3. Now, no matter where I open Firefox, it gets pinned to workspace 3, and is at most a couple CTRL+direction keystrokes away.

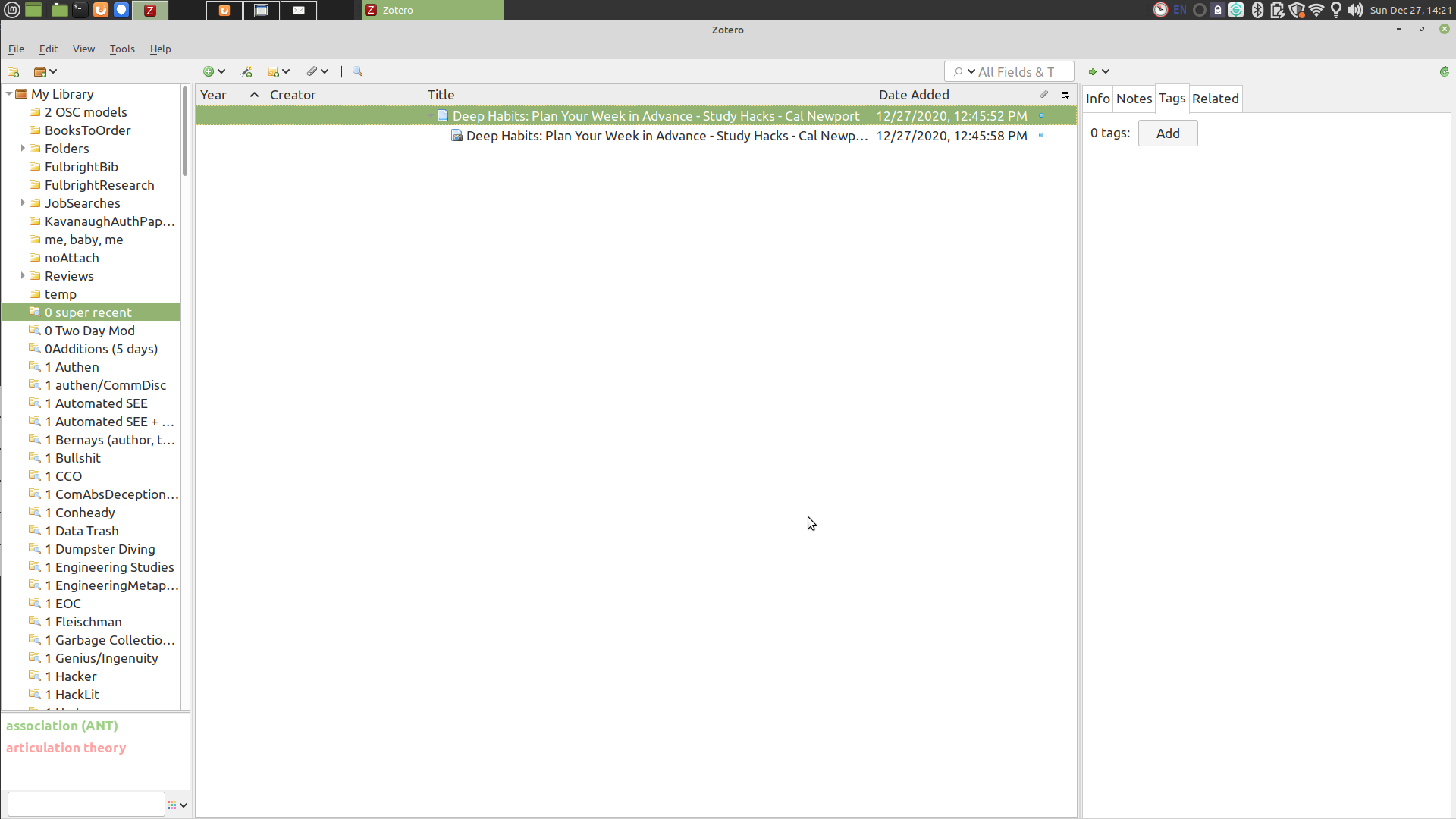

Using similar techniques, I route my applications to the same places -- Zotero, the citation manager, goes in Workspace 1. My "comms" workspace is 5, with Evolution email and chat applications routed there. Entertainment (music players, video players) goes to 6. Terminals and my IDE (currently Brackets) goes to 4.

With the exception of Brackets going to 4, most of my writing goes into Workspace 2. I route Libreoffice there, as well as my PDF reader. I also use some rules to move Zotero notes to Workspace 2. Devilspie allows me to control window geometry, so I set my PDF reader to 2/3s of the screen and a Zotero note to the remaining 1/3. Devilspie even supports "always on top", though I don't use that much.

I'm a bit concerned, however. The original devilspie is apparently no longer being maintained, and neither is its successor, Devilspie2. I hope these handy applications stick around!

But for now, with devilspie and the corresponding rules in place, when I launch an application (in my case, using Synapse, which appears with CTRL+Space), I know exactly which workspace it's routed to. I can flip between a browser and a writing application with a keystroke -- cutting, pasting, and so on.

Pomodoro

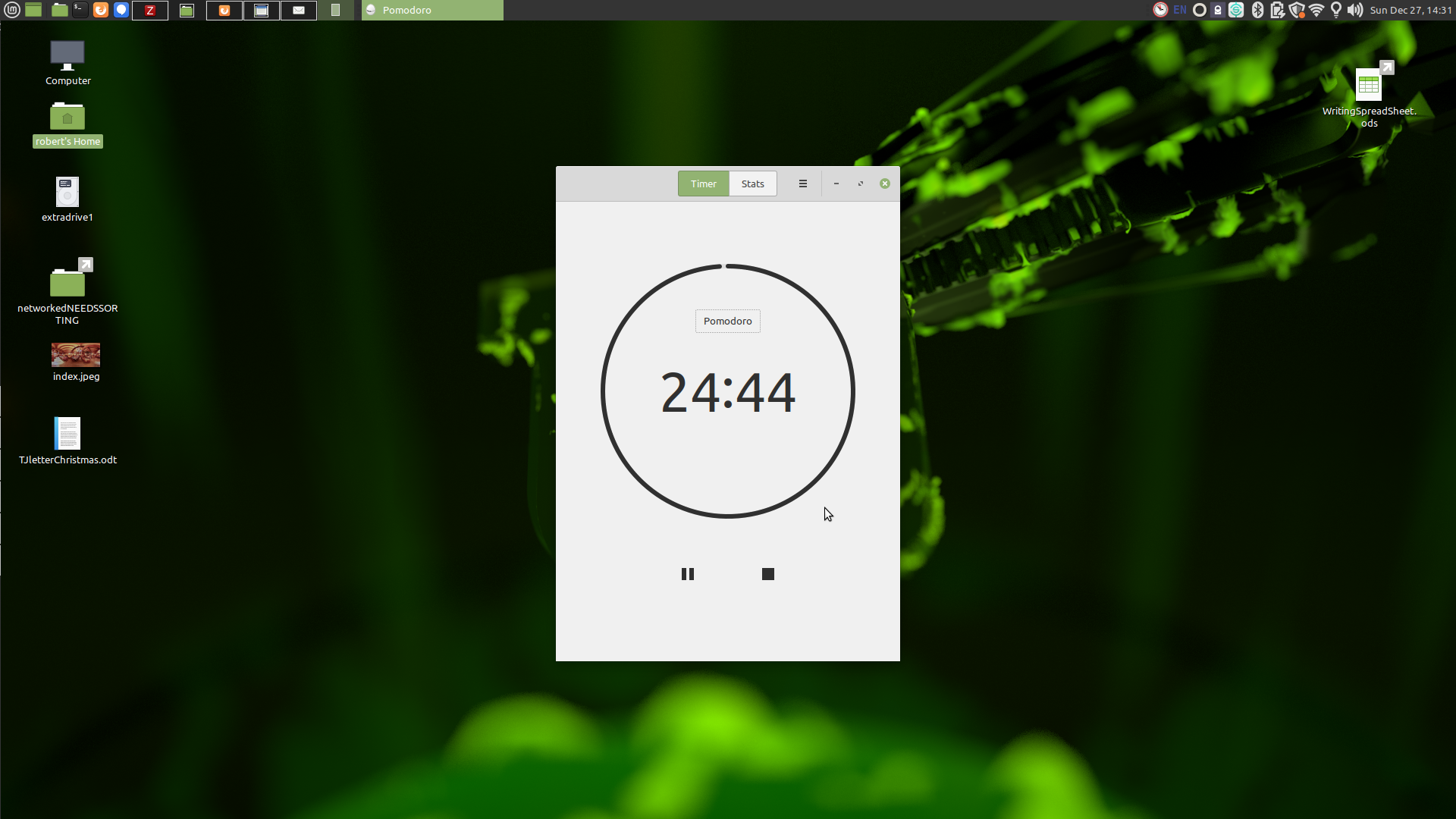

In fact, switching from my writing space Workspace 2 to email or a Signal message in Workspace 5 is now too easy. Distraction is just a couple CTRL+Rights away. I find myself flipping over to email too often, and for no good reason. Because of this, I close Evolution and Signal, but to really help me focus, I also use the Pomodoro Timer for Gnome.

I find the Pomodoro Technique to be a simple and effective way to stay on task. It starts with a conscious decision to say "I am working on this task." Then, I start the timer (set to the default 25 minutes) and do it. After 25 minutes, the Pomodoro Timer takes over my screen and says, "Take a break!" I take the 5 minute break to stretch, do some pushups, move my limbs. And then: back at it for another 25. If I do four Pomodoros, I take a longer, 15 minute break, usually by walking around campus.

The nice thing about this approach is that it is open-ended. If I have a stack of emails: that's the task. Once that's done, I can switch to grading, or writing. 25 minutes seems like a good amount to knock out a lot of things.

But how to decide which tasks need be done?

Cal Newport's Weekly To-do List: Workspace 5

I don't think Cal Newport came up with the weekly work plan, but I give him credit because I first learned it from his blog. As he writes,

On Monday mornings I plan the upcoming work week. I capture this plan in an e-mail and send it to myself so that I will be sure to see it and have access to it daily.

I used to do it via email, but now I put a task in Evolution. Every Monday morning, I spend about an hour assessing what I need to get done in the week, and then I develop a weekly schedule with time blocks allotted to the various tasks. I set the task to be "due" on Sunday. I don't actually look at it then; I instead look back on last week's plan on the subsequent Monday morning, reflecting on what I got done in the previous week. I also use the Sunday deadline to see if any tasks in Evolution are due sooner than my weekly schedule -- that means those tasks are high priority for the week.

At the top of my weekly plan I list out projects I'm working on. Usually, these are long-term projects which require daily work to maintain progress towards deadlines.

I then break the week down by day and assign blocks of time (typically an hour or two) as time to drive towards completing those long-term goals.

A week then looks like this:

2020 December 13

//Research

* WP met Tor

* Mastodon

* JOC

* DNS

//Teaching

* Comm 431:

- Build at least one more week

- grading

* Comm 101

- find podcast episode

- grading

//Service

* NMS review

## Monday 13 Dec

2 hours DNS research and writing

1 hour Comm 431

1 hour Comm 101

## Tuesday 14 Dec

2 hours DNS research and writing

1 hour Comm 431 grading

1 hour NMS review

## Wednesday 14 Dec

2 hours research

1 hour email

...etc, etc

You'll notice I'm following Newport's advice to keep it flexible. Not every moment of the week is planned, but I do allot a good amount of time to "deep" tasks like writing. (And if you're thinking that this will work well with Pomodoro -- you're right!). For me, I can do about 2 hours of intense writing a working day, so that's all I schedule.

Speaking of flexibility, I also like having at least 2 writing projects at a time -- I agree with Manya Whitaker's suggestion to have a couple projects in order to switch from one when I inevitably get sick of it. (There is nothing better for writing, I find, then putting what I've written away for a while and coming back to it later.)

The rest of my day I tackle other tasks -- "urgent" emails, grading, course prep.

Writing Routine: Workspace 2

As you can tell, my work centers on writing. I do most of my work in Workspace 2. So let me say a bit more about that.

The biggest thing I do is "pay myself first" -- that is, whenever possible, I write first. If I have an early class, of course, I get ready to teach that, but my drive is always "write first" in a given day. Writing journal articles or books is a long-term practice that can feel like there's no immediate payoff. That's a danger, because knocking out 25 emails or grading 25 papers has an immediate payoff. The problem is that I have finite energy, and I spend a few hours on grading or emails, I will not be in the mood to do any deep writing. So, writing comes first.

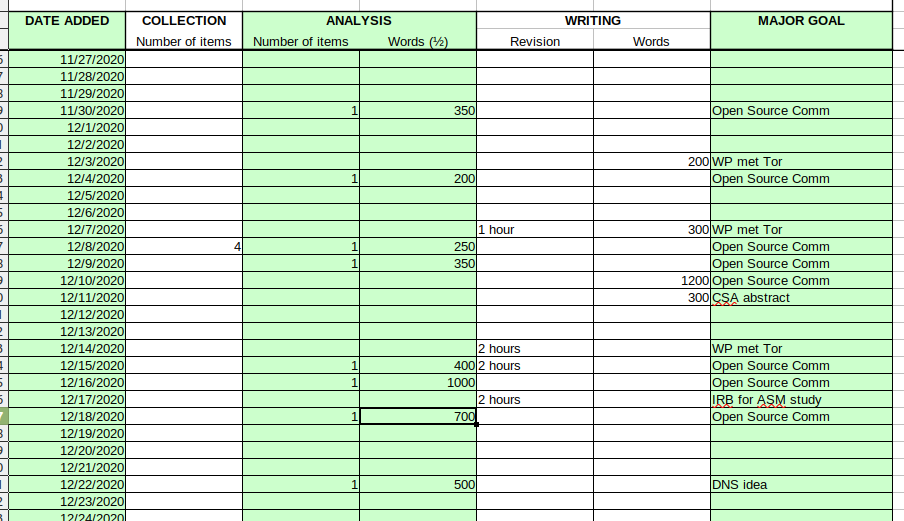

Related to this: because answering an email has that immediate payoff (yay! another email answered!) and writing can feel like a long slog, I give myself credit for my daily writing. I keep a log of how many words I write in a day (a habit I think I picked up after reading about John Steinbeck's habits). I have a daily goal of 500 words a day. I can usually do that in two hours. I keep a log of these words in a LibreOffice spreadsheet, and I monitor my writing goals on a fortnightly basis.

You may ask: 500 words a day? What if they suck? Aren't you just setting yourself up to just write 500 bad words to fulfill some arbitrary goal?

Well... maybe. But -- and I can't emphasize this enough -- you don't know if the words are any good until you write them. They have to exist to be judged. By keeping track of my daily writing, I've learned over the years that probably 1/10th of my writing ends up actually getting published. The rest ends up on the proverbial "cutting room floor." But I don't get to publish the 10% if I don't write anything in the first place.

In other words: I don't believe in inspiration. Practice. Yes, AI, I'm talking about practice.

You may also ask: what about taking notes? I consider that writing, so it counts (though I usually count half of my note-taking words). Taking notes is definitely writing -- reading a journal article or book sparks ideas, and of course I must cite and build upon sources. So that counts, too.

You may finally ask: what about revision? Surely you cut words. Do you count them as negative word counts?

No. If I'm revising, I give myself credit for hours I spend doing that. Revision is so important that it gets its own column in my spreadsheet.

Conclusion

So, there you have it. My workflow using FOSS tools -- MATE Desktop, devilspie, Evolution, Zotero, Libreoffice. Weekly plans, long-term projects, and daily writing goals.

It's worked quite well for me over the 2010s. I've written three books, a couple dozen journal articles, and a range of other publications, all while teaching courses and doing service.

So, I think it will work well into the 2020s. I think I can use this process to drive towards Goal 2: my next book. A FOSS book.